On Feb. 1, 2004, GetReligion co-founder Doug Leblanc opened the digital doors here at GetReligion and our first post went live. The headline: “What we do, why we do it.”

I tweaked that post a bit in 2019, but left the main point intact. The key was that GetReligion was going to try to spot what I called religion “ghosts” in hard-news stories in the mainstream press. What, precisely, was a religion “ghost”? I raise this issue once again because this week’s “Crossroads” podcast (CLICK HERE to tune that in) focused on a “ghost” question in a very important topic in the news. Hold that thought.

That first post opened with Americans sitting down to read their newspapers or watch television news.

They read stories that are important to their lives, yet they seem to catch fleeting glimpses of other characters or other plots between the lines. …

One minute they are there. The next they are gone. There are ghosts in there, hiding in the ink and the pixels. Something is missing in the basic facts or perhaps most of the key facts are there, yet some are twisted. Perhaps there are sins of omission, rather than commission.

A lot of these ghosts are, well, holy ghosts. They are facts and stories and faces linked to the power of religious faith. Now you see them. Now you don’t.

This brings us to a recent Associated Press report with this headline: “Army cuts force size amid unprecedented battle for recruits.” There are zero references to religion in this report, which is kind of the point.

Is there a religion “ghost” somewhere in this story? Here are some crucial paragraphs:

With just two and a half months to go in the fiscal year, the Army has achieved just 50% of its recruiting goal of 60,000 soldiers, according to Lt. Col. Randee Farrell, spokeswoman for Army Secretary Christine Wormuth. Based on those numbers and trends, it is likely the Army will miss the goal by nearly 25% as of Oct. 1. …

The military services rely heavily on face-to-face meetings with young people in schools or at fairs and other large public events. And they are only now really starting to get back to something close to normal after two years of the [COVID-19] pandemic.

Compounding the problem is the low unemployment rate and the fact that private corporations may be able to pay more to lure workers. And, among young people, only about 23% are physically, mentally and morally qualified to serve without receiving some type of waiver.

This story argues — with good cause — that U.S. military recruiters are struggling for several obvious reasons.

The pandemic is one of them. I would note that when recruiters, with their focus on students coming out of high school, face the same problem as most colleges and universities — a large drop in the number of candidates for reasons linked to birth rates and demographic issues after the large Millennial generation.

As noted, there are also fewer young Americans who can (think obesity rates and video-game addictions) clear the already modest physical fitness requirements for entering the military.

It also appears that many young Americans are, well, afraid to enter military service. The term “triggered” leaps to mind. See this chunk of a 2020 NBC News report:

An internal Defense Department survey obtained by NBC News found that only 9% of those young Americans eligible to serve in the military had any inclination to do so, the lowest number since 2007.

The survey sheds light on how both Americans’ view of the military and the growing civilian-military divide may also be factors in slumping recruitment, and how public attitudes could cause recruiting struggles for years to come.

More than half of the young Americans who answered the survey — about 57% — think they would have emotional or psychological problems after serving in the military. Nearly half think they would have physical problems.

I am getting closer to my religion “ghost” questions. It does appear that many Americans are not willing to consider military service.

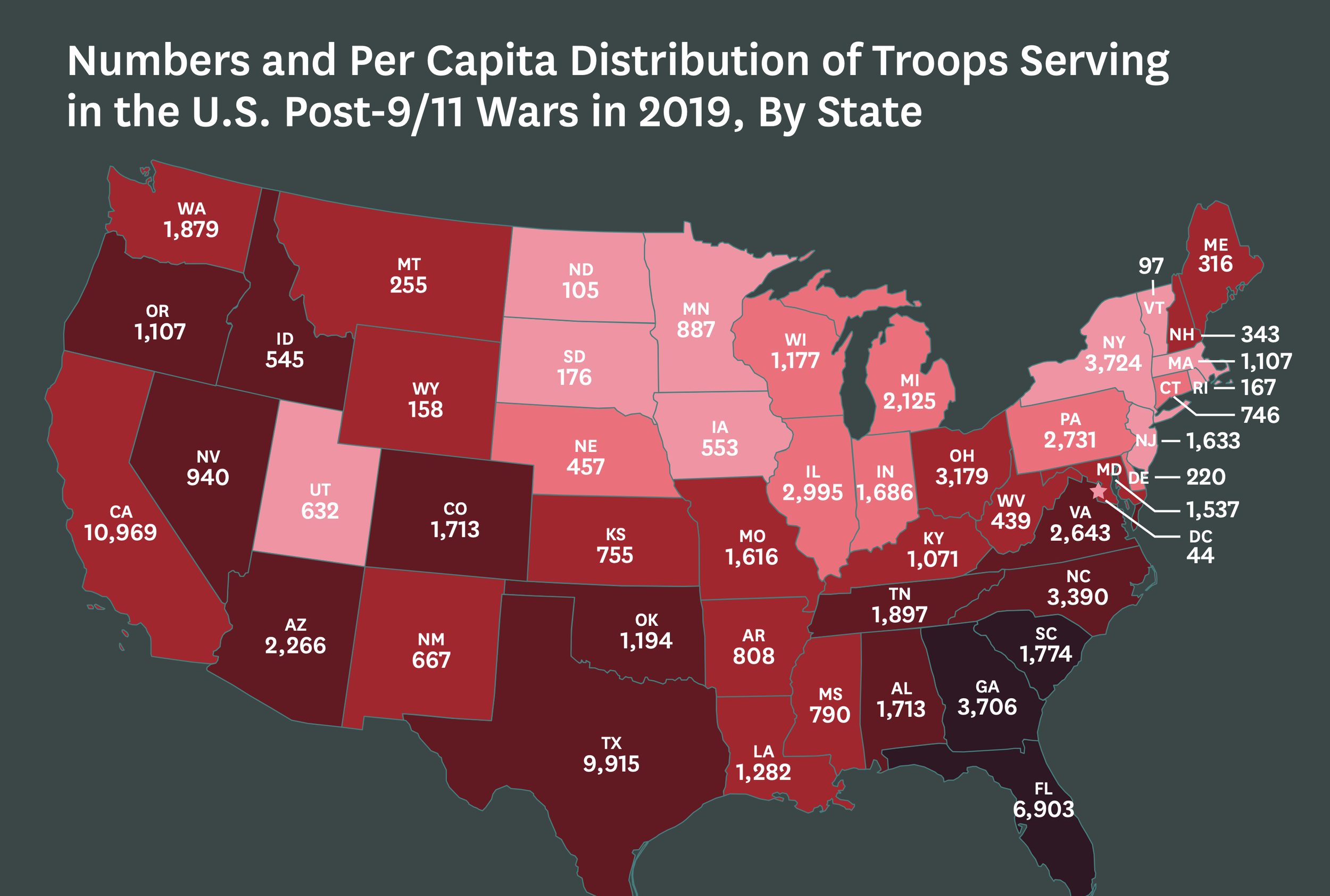

What about the families that, in the past, were more than willing to serve? What is happening with them? Also, where — in the United States of America — do the vast majority of these families call home? (See the .pdf map at the top of this post, drawn from materials at the “Cost of War” collection at the Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs at Brown University.)

According to a recent New York Times report, there are zip codes that produce military recruits and those that, for the most part, do not. And there are other patterns to note, producing patterns that have:

… made the armed forces something of a family business, and led to some communities, many of them in the Southeast, supplying a disproportionate share of recruits. But even in those kinds of communities, recruiting has been tough this year.

The city of Fountain, a few miles from Fort Carson, is a patchwork of working-class neighborhoods with strong military ties. But the recruiting station here has not met its goals for three months.

Let’s back up two years and look at another New York Times story, one that ran with this very informative double-decker headline:

Who Signs Up to Fight? Makeup of U.S. Recruits Shows Glaring Disparity.

More and more, new recruits come from the same small number of counties and are the children of old recruits.

Again, there are patterns that can be seen on a map. To be blunt, these patterns resemble — especially when looking at counties and zip codes — the familiar “red” vs. “blue” divides linked to rural vs. urban life, as well as the maps contrasting “Jesusland” with “The United States of Canada.”

At the very least, this term is relevant — “Bible Belt.”

The men and women who sign up overwhelmingly come from counties in the South and a scattering of communities at the gates of military bases like Colorado Springs, which sits next to Fort Carson and several Air Force installations, and where the tradition of military service is deeply ingrained.

More and more, new recruits are the children of old recruits. In 2019, 79 percent of Army recruits reported having a family member who served. For nearly 30 percent, it was a parent — a striking point in a nation where less than 1 percent of the population serves in the military.

For years, military leaders have been sounding the alarm over the growing gulf between communities that serve and those that do not, warning that relying on a small number of counties that reliably produce soldiers is unsustainable.

Apparently, the key issues are not linked to race or social class. The story includes this summary quotation from Kelli Bland, a spokeswoman for the Army’s Recruiting Command: “Those who understand military life are more likely to consider it as a career option than those who do not.”

This leads me to my main question: Are there trends that are causing pro-military families in “red” American zip codes to lose faith in the various branches of the U.S. armed services?

As stated earlier, there appear to be economic and health trends that are making it harder for military recruiters to do their jobs. My question is whether there are religious, moral and cultural issues in play. Yes, there may be overlapping political issues, as well.

As you would expect, blogger Rod “Live Not By Lies” Dreher has no doubts about what is happening. See this post: “What Are Military Recruits Defending? Conservative Christians are no longer encouraging their children to join the armed forces, and why should they?”

Dreher hears from pro-military readers all the time who are concerned about “woke” trends in the armed services, many having to do with LGBTQ issues. Are these concerns valid? That’s a question worthy of serious journalism, with reporters and editors offering accurate and fair-minded coverage of mainstream voices on both sides of these debates.

Frankly, I have — for the past decade of two — received more than my share of emails from similar readers. Many come from U.S. military chaplains. In recent decades, more than a few evangelical Protestant chaplains (and others) have claimed that they were denied promotions because they have declined to (a) use prayer language in public events that clashes with the teachings of their churches and denominations and (b) lead marriage-preparation classes that include same-sex as well as opposite-sex couples.

Now, if you have followed church-state debates in recent decades, you know that the U.S. government’s tradition of hiring military chaplains is controversial — period.

Here are some valid questions: How large does a faith group need to be to have its own chaplains (think neopagans, atheists and others)? Should the military hire chaplains that — for theological reasons — cannot serve soldiers whose beliefs are the opposite of their own? Flip that around: Can the military REQUIRE chaplains to violate the doctrines of the traditions that authorize their service?

Consider this question that I asked in the podcast: Can a Catholic soldier go to Confession if the only chaplain available is, let’s say, an Episcopalian (male or female) or a Baptist (male or female)?

Here is another sensitive issue that has received coverage in (#DUH) conservative media. This is drawn from a April 20, 2021 Department of Defense memo posted online (.pdf here):

Gender transition begins when a Service member receives a diagnosis from a military medical provider indicating that gender transition is medically necessary, and then completes the medical care identified or approved by a military mental health or medical provider in a documented treatment plan as necessary to achieve stability in the self-identified gender. It concludes when the Service member’s gender marker in DEERS is changed and the Service member is recognized in his or her self-identified gender. Care and treatment may still be received after the gender marker is changed in DEERS as described in Paragraph 3.2.c. of this issuance, but at that point, the Service member must meet all applicable military standards in the self-identified gender. With regard to facilities subject to regulation by the military, a Service member whose gender marker has been changed in DEERS will use those berthing, bathroom, and shower facilities associated with his or her gender marker in DEERS.

The key phrases, of course, are “self-identified gender” and “berthing, bathroom, and shower facilities.”

Message received. That message will be more popular in some zip codes than others.

Many families will embrace this policy. Many will not.

Many mainstream religious groups (and their chaplains) will have zero problem with the moral and theological implications of that policy. However, there are others that will reject it — period — based on centuries of doctrine and tradition.

In conclusion: Am I arguing that the current problems experienced by military recruiters are rooted in religious, moral and cultural issues, alone? Is this THE key factor in this trend?

I am not. That would be simplistic and inaccurate. There are many important factors at play in this story. However, I am arguing that religious, moral and cultural issues appear to be ONE factor that is shaping this crisis.

Thus, there is a religion “ghost” in this story. Journalists should consider talking to chaplains in traditional religious faiths — bodies that have, in the past, provided many, many chaplains — to learn if they are hearing questions from parents, pastors and their denominational leaders.

The bottom line: Should journalists cover this angle of the story? Why or why not?

Enjoy the podcast and, please, pass it along to others.

FIRST IMAGE: Pride month illustration used by U.S. military in various social media outlets.