How old does a “think piece” need to be for people to stop thinking about it?

Let me state that another way: What if a “think piece” is a year old and I am still thinking about it?

Part of my logic, in this case, is that discussion of certain topics linked to this particular Religion in Public blog piece have, if anything, only heated up in the 12 months since it was posted. Consider the urgent push for reporting, publishing and polling about “Christian nationalism,” which has almost turned into an industry of its own, especially in certain niche corners of the press.

Oh, has the Associated Press ruled on whether the “n” in that term is upper- or lower-case? If this is a movement, it really needs its own website and corporate headquarters, or is that like asking for official contact information about the Mafia?

Anyway, this brings me to a really interesting piece by researcher Paul A. Djupe of Denison University, who is best known in these parts as a frequent co-writer with Ryan Burge, a contributor to this website. Here is the headline: “Congregations are Doing Acceptable Amounts of Political Engagement.”

The question at the heart of the essay: Do people who claim to want churches to stay out of politics include their own for of organized religion (and maybe unorganized sort-of religion)? Djupe is reacting, in part, to a Pew Research study posted online with this headline: “Americans Have Positive Views About Religion’s Role in Society, but Want It Out of Politics.”

So here is the first major chunk of material that readers — journalists especially — need to think about.

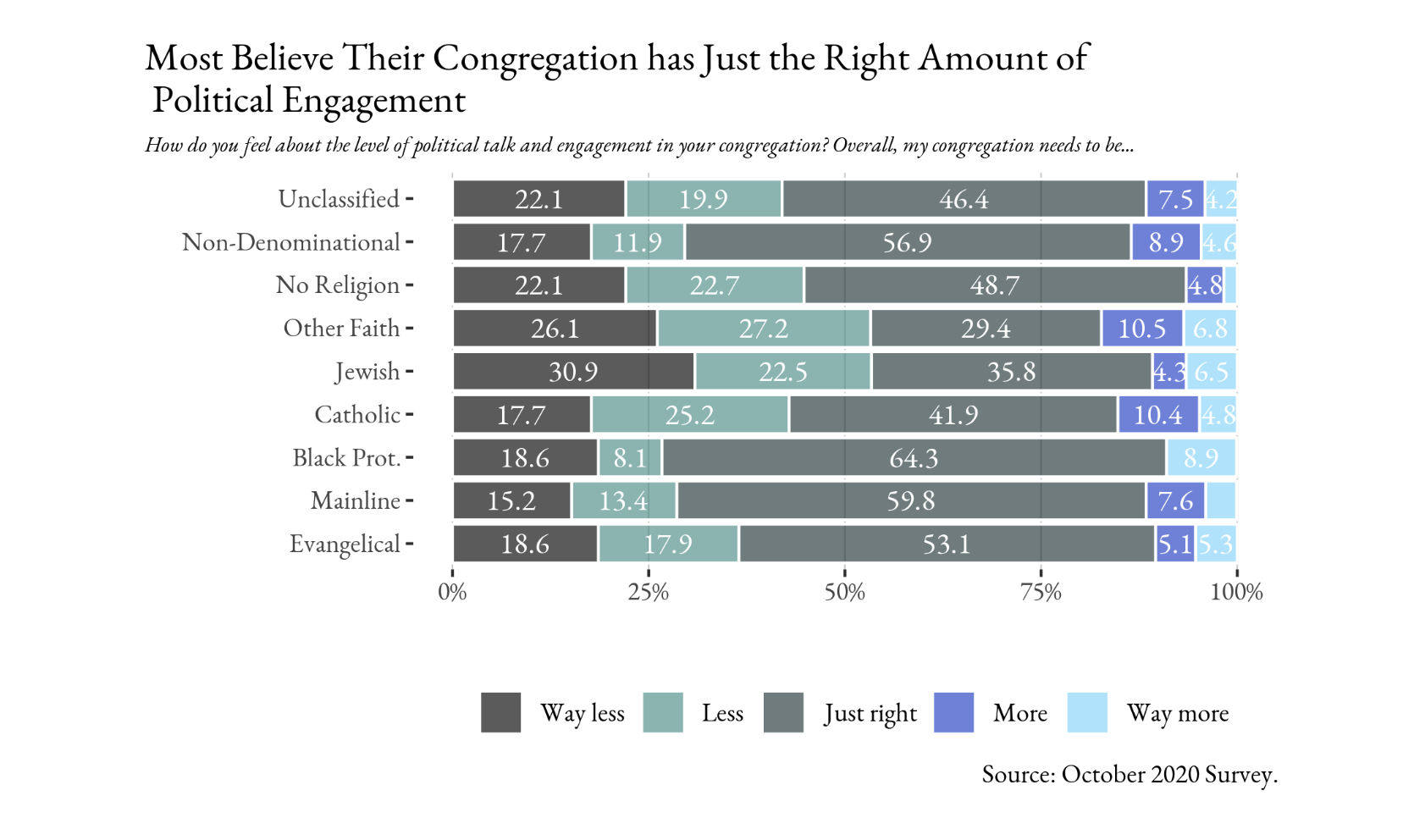

In October 2020, at the height of the voting phase of the presidential election, we asked 1,306 worship attenders about the level of political engagement in their house of worship, soliciting whether the congregation needed to be less political, more political, or had just the right level of political engagement. The (weighted) response is almost the exact opposite of the Pew result from a few years ago — 60 percent believe their congregation was just right or should be more political, while 40 percent say it should be less (or way less) political.

The distribution of these responses by religious tradition is below and shows that almost every tradition is comfortable (combining the just right + more responses) with the level of politics in their congregations, with the exception of the religious minorities in the sample (Jews and “other faith” which includes Buddhists, Hindus, Muslims, and others). It is no surprise that Black Protestants are the most comfortable – three quarters say it is just right or want more — with mainline Protestants and nondenominationals following just behind.

Once again, reporters need to grasp that Americans on the religious and cultural left are more active in politics than those on the Religious Right. Yes, we know — after kazillions of reports over several decades — that this crowd on the conservative side of things deserves the upper-case label.

Let’s keep reading:

This pattern presents a bit of a problem, since mainline congregations are somewhat less politically engaged than Black Protestants both historically and in this survey data. In fact, Black Protestants are near the top end of hearing political topics from their clergy while mainliners are at the bottom (though not at zero). What we also know about these two religious traditions is that Black Protestants tend not to disagree with their clergy, while mainliners are likely to.

Yes, at some point you know that Christian nationalism will come into play when discussing these topics, so let’s let Djupe connect a few dots.

By the way, this is not really a Donald Trump thing. He sees patterns that are bigger than that.

We … need to consider the threat environment (perceived or real). While conservative Christians once had far less support for congregational political involvement, that is no longer true and has not been for awhile. These days, the centrality of Christianity is in question due to demographic change and increasing rates of disaffiliation. So it is no surprise that ardent Christian nationalists, who conflate the interests of Christians with the US, are much more likely to be comfortable with their congregation’s political involvement (they are also more likely to report their clergy addressing political topics, so this isn’t support for quietism).

Perhaps one of the explanations for that link with Christian nationalism is that they are hearing that Christians are and will be persecuted in the US if they are not in control of the government. Not surprising, beliefs that Christians are being persecuted are linked with comfort with the congregation’s politics.

OK, so there are Christian conservatives who believe that persecution is real and it’s safe to say that this flock is larger than cake bakers and florists in deep-blue zip codes.

But what is firing up folks on the other side? Maybe there is a chance that the more “mainline” believers also have reasons for their higher levels of political activism and their comfort with their churches diving into the fray?

I’d be interested in seeing more questions about that.

It is clear that the Big Idea here is something for people on the left as well as the right to take seriously. Thus, read this thesis statement more than once:

There’s a simple story out there that Americans don’t want religion mixing in politics. The reality is that they don’t want other people’s religion mixing with their politics. Instead, they tend to support their own congregation’s involvement and only a minority want less of it.