One of the true gifts of being a quantitative social scientist in 2023 is that I get to stand on the shoulders of the giants who came before me.

A handful of scholars fought hard to get a series of religion questions added to the General Social Survey when it was first fielded in 1972. Then they had to fight to keep those questions on there over the last five decades.

I wouldn’t be able to do this kind of work without the unnamed and all too quickly forgotten contributions of those academics who knew that those kinds of questions were going to be useful someday. This post is a tribute to those efforts to trace American religion since the early 1970s.

After staring at this data for the last decade I wanted to compile four examples of trend lines in the data that still blow my mind. These are short little periods of time when American religion changed dramatically and has largely been overlooked. I think they can offer some insights into how American culture has shifted in the last couple of decades.

The Evangelical Surge (1983-2000) — It feels like evangelicals are everywhere. Hardly a week goes by without some type of national news story about what they are up to, but that’s especially the case when an election draws near. No denominational gathering is covered as extensively as the Southern Baptist Convention’s annual meeting. People, for whatever reason, are just fascinated (and sometimes horrified) by evangelical Christianity.

But, if you look at the share of Americans who were evangelical in 1980 and in 2018, there’s basically been no change. They were 24% in 1980 and about 23% in 2018. The same is true when look at 1983 and 2000. About 23% of America in those two years.

But between those two dates, evangelicalism experienced an unbelievably swift rise and then an even faster decline. Between 1983 and 1993, evangelicalism grew by 6.6 percentage points. Then, in the next seven years, it gave back almost all those gains by losing 6.3 percentage points. At its peak, three in 10 American adults were evangelicals.

I have to admit to a personal stake in all of this. I was born in 1982 and was a faithful attender of a Southern Baptist Church until 2002 or so. Which means I had a bird’s eye view of the ascendance of evangelicalism. What drove this big jump? I’ve got a few theories.

Televangelism was really going strong during this period of time. The Revs. Pat Robertson and Jerry Falwell were both on TV constantly for their preaching and their politics. Billy Graham was still vibrant enough to preach revivals all over the world.

The Religious Right was also energized and engaged. They enjoyed eight years of the Reagan presidency then another four years of George H.W. Bush in the White House. I don’t think it’s any coincidence that evangelicalism rose during those twelve years of GOP presidents.

Also, evangelical culture was just so pervasive during that time period. There were Christian artists who had huge albums that hit the mainstream like dc Talk’s Jesus Freak and Jars of Clays self-titled debut, which were released a month apart in late 1995. There were Christian musical festivals that attracted tens of thousands and non-denominational churches were just sprouting up in suburbs across America.

It’s unlikely that evangelicalism will ever reach those heights again. But, as I pointed out in Chapter 1 of my book “20 Myths about Religion and Politics in America,” evangelicals are a larger share of the United States today than they were in 1972. Sure, they are down from their peak in 1993, but they are still a force to be reckoned with in American society and politics.

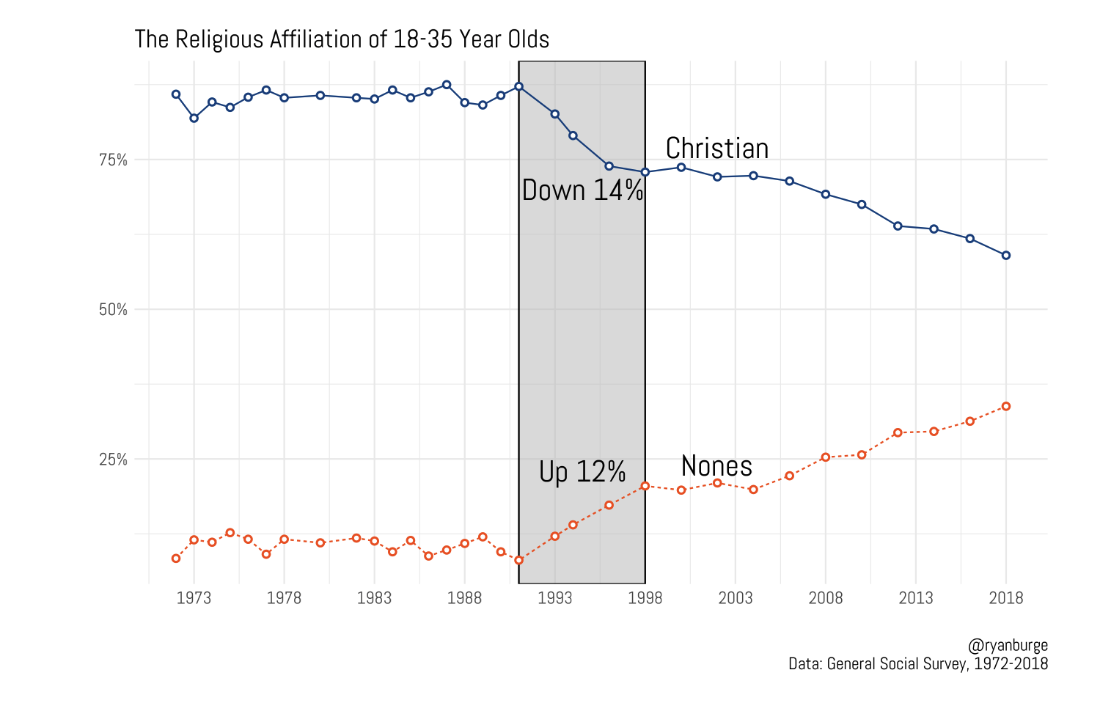

Young People Lose Their Religion (1991-1998) — That first graph absolutely sets the stage for this second one. I am only considering people between the ages of 18 and 35 years old here. Just look at how straight those lines are between 1972 and 1990. The wiggles are never that big (in either direction). Just a steady 85% of young folks who identify as Christians and about 12% who no religious affiliation.

Then, 1991 happens and everything begins to change. Very rapidly. Between 1991 and 1998 and share of young folks who identify as Christians dropped from 87% to 73%, while the share who had no religious affiliation rose from 8% to 20%. All in a span of seven years. That’s an insane level of growth/decline in such a short period of time.

One could say something like: well, a lot of people aged out of the 18–35-year-old category in those eight years and a lot of younger folks moved into adulthood. That might explain some of it, but it certainly doesn’t explain all this movement so quickly. And also, why didn’t that same level of generational churn not show up at that same rate before or after this little window of time in the 1990s?

There has to be something unique happening between 1991 and 1998 that caused a lot of young folks to flee the pews and join the ranks of the nones. I’ve written about this at length for Religion News Service, but I will briefly summarize that here.

Political Polarization. The Republicans won the House in huge numbers by following the example of Newt Gingrich who delighted in demonizing the Democrats. They weren’t just wrong on policy, they were evil. That meant that people felt like they need to pick a side. For many marginally attached religious folks, that was the nudge they needed to walk away from their church.

The Cold War ended. The conflict between the United States and the USSR was oftentimes described in religious terms. It was the God fearing, freedom loving capitalists at war with the godless, communists. “Under God” was added to the Pledge of the Allegiance in “In God We Trust” was included on the currency in the 1950s, largely to make this point plain. The United States were Christians, the Soviets were atheists. Then the Berlin wall fell. The stigma against atheism began to fade a bit.

The Internet. This is one that feels so descriptive, but I have not found a way to actually test this one with any data. A big reason is because a huge chunk of America got home internet in a very brief period of time. Thus, there’s no really good “control” group. And even then, there’s a bunch of socioeconomic factors that drove some families to get broadband earlier than others. So it would be apples to oranges. But there’s no doubt in my mind that young people began researching their own faith, as well as what other religions believed. That was enough for some to throw their hands up and walk away entirely.

The Explosion of the Nones (1991-2010) — Sometimes digging through scholarly archives can yield tremendous stuff. Glenn Vernon wrote a paper that was published in 1968 entitled, “The Religious ‘Nones’: A Neglected Category.” Glenn was on to something, he just happened to be about twenty-five years too early. Between 1972 and 1991, the share of Americans who claimed no religious affiliation rose just 1.2%. That’s nothing more than a blip. Just statistical noise that would have likely been imperceptible to the average person.

The next 19 years offer a dramatically different picture of the nones. They were about 6% of the sample in 1991. By 1994, that had jumped to nearly 9%. And the gains didn’t stop there. By 2000, that figure was 14%. By 2010, the nones were now 18%.

In the most recent data that I have from the GSS, the nones are just about 29%. That’s essentially a five fold increase in three decades. I say this all the time but it’s worth repeating — the rise of the nones and “none of the aboves” may be the most significant shift in American society over the last 30 years.

There’s no doubt that the graph before this is explanatory when it comes to the rise of the nones. Remember, those are people who were 18-35 years old in the early 1990s. Which means a significant share of them have had children by now. Those children were much more likely to be raised without religion than any prior generation.

I can write another thousand words about the rise of the nones, but I would just ask that you consider buying “The Nones, 2nd Edition.” It’s chock full of data and explanations for the rise of the non-religious.

The Collapse of the Mainline (1975-1988) — For those who are not familiar with the term “mainline Protestants” it’s the non-evangelical flavor of (primarily) white Protestant Christianity. Think of the United Methodists, the Episcopalians, and the United Church of Christ. According to James Hudnut-Beumler, in “The Future of Mainline Protestants,” a majority of all Americans were aligned with a mainline tradition in the late 1950s.

Theologically, they are more moderate than evangelicals. All the major denominations in the mainline allow women pastors and are open and affirming to same sex couples. I recommend this piece for a deeper dive into the mainline: “What is a Mainline Protestant?”

With that backdrop, let me point out something that is absolutely mind boggling about the mainline. In 1975, they were nearly 31% of all adult Americans (recall that they were 51% in the late 1950s). But in the next thirteen years, the share of Americans who were mainline dropped twelve percentage points, landing at 19% in 1988.

That’s tens of millions of Americans leaving the pews of the mainline in just over a decade. And they have never really recovered from that point, but the decline has slowed considerably. In the thirty years since 1988, the mainline lost a total of nine percentage points. Twelve points in thirteen years. Then, nine points in 30 years. That’s how fast, then slow the decline really happened.

This is one that I am still trying to conceptualize in my mind.

CONTINUE READING: “Four of the Most Dramatic Shifts in American Religion Over the Last 50 Years” at the Substack feed of Ryan Burge.